Garry Rogers

Abstract

Land-use changes dominated biodiversity decline throughout the 20th century, but scientific evidence indicates climate change will probably become the primary driver by mid-century. Complex feedback mechanisms between climate change and biodiversity create self-reinforcing cycles of degradation. Marine ecosystems face severe threats. Coral reefs could decline by 70-90% even if warming is limited to 1.5°C. Terrestrial ecosystems are also undergoing profound transformations. Nearly 40% of land-based ecosystems may convert to different types by 2100. These changes threaten human well-being through diminished ecosystem services valued at trillions of dollars annually. Despite scientific uncertainties, the direction and severity of these trends remain consistent across diverse research approaches. Addressing this crisis requires integrated conservation and climate policy. Traditional protected area strategies must evolve to incorporate climate resilience and connectivity. The next five years are critical for determining future biosphere trajectories. While some ecosystem transformation is inevitable given committed warming, ambitious climate action and strategic conservation investments could substantially reduce biodiversity decline. This challenge requires unprecedented cooperation across scientific disciplines, policy domains, and national boundaries.

Introduction

Earth’s biosphere is undergoing unprecedented decline. Land-use changes caused significant biodiversity losses in the 20th century. However, recent studies show climate change will probably become the dominant driver of biodiversity loss by mid-century (Pereira et al. 2024). This shift has profound implications for ecosystem services crucial to human society. It requires urgent scientific attention and coordinated policy responses.

The Changing Face of Biodiversity Loss

Historical patterns of biodiversity decline centered on habitat destruction. Global biodiversity declined between 2% and 11% during the 20th century from this factor alone (Pereira et al. 2024). This trend mirrors human development expanding into natural areas. The conversion of forests into agricultural land is especially notable. Satellite observations show field crops expanded onto an additional one million square kilometers during just the past two decades. About half of this newly converted area replaced forests and other natural ecosystems (Potapov et al. 2021).

Climate change accelerates this pattern. It also introduces new threats through multiple mechanisms. Rising temperatures exceed physiological tolerances, disrupt ecological relationships, and alter habitat conditions (Bellard et al. 2012). The Great Barrier Reef experienced four mass coral bleaching events in just seven years. This reduced shallow water coral cover by as much as 50% (Great Barrier Reef Foundation 2024).

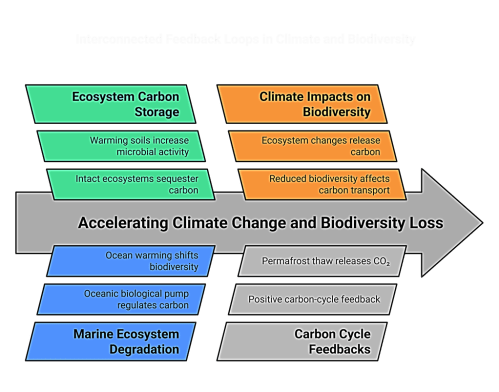

Feedback Mechanisms Accelerating Decline

The relationship between climate change and biodiversity loss involves complex feedback mechanisms. These risk accelerating both processes. Individual biosphere integrity mechanisms may not outweigh existing climate-carbon cycle feedbacks. However, their combined effects generate a positive carbon-cycle feedback. This might add 0.1°C or more of warming. This estimate holds across multiple emissions scenarios (Malhi et al. 2020).

One crucial feedback loop involves ecosystem carbon storage. Intact ecosystems sequester significant amounts of carbon. Climate change impacts reduce this capacity. For instance, warming soils increase microbial activity. This accelerates carbon decomposition. It releases stored carbon as CO₂. Recent studies suggest permafrost thaw alone could release substantial carbon. This might trigger additional warming beyond current projections (Malhi et al. 2020).

Marine ecosystem degradation reduces the ocean’s carbon absorption capability. The oceanic biological pump currently helps regulate atmospheric carbon levels. Ocean warming and acidification shift marine biodiversity toward smaller organisms. These are less effective at transporting carbon to deeper waters (Beaugrand et al. 2010). Scientists predict the biological pump could weaken by approximately 12% by 2100 under high-emissions scenarios. This is primarily due to increased ocean stratification. It reduces nutrient delivery to surface waters (Bopp et al. 2013).

These feedback loops create troubling dynamics. Initial climate-driven ecosystem changes cause additional carbon releases. This leads to further warming. It creates a potentially escalating cycle of degradation (Malhi et al. 2020). This self-reinforcing pattern explains why climate and biodiversity protection efforts must be viewed as interconnected. They are not separate environmental concerns.

Threats to Marine Ecosystems

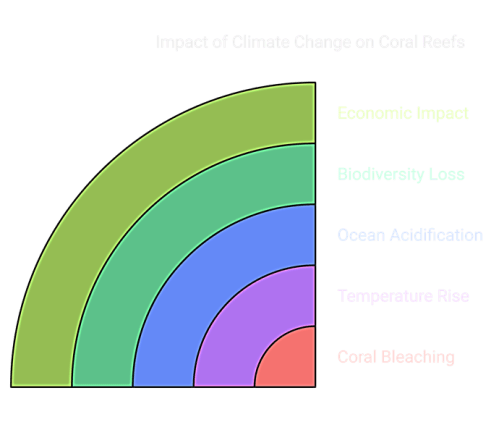

Ocean systems face severe climate-driven threats. Rising temperatures trigger coral bleaching events with increasing frequency and intensity. When water temperatures rise too high, corals expel their symbiotic algae. They lose their primary energy source. Their white calcium carbonate skeletons become visible. This process is called bleaching (NOAA 2024). Bleached corals can recover if conditions improve quickly. However, prolonged or repeated bleaching leads to widespread mortality.

The statistics on projected coral reef decline are sobering. According to the IPCC, limiting global warming to 1.5°C would still result in a 70-90% decline in coral reefs globally. If temperatures rise by 2°C, over 99% of coral reefs could disappear (Science Feedback 2024). This vulnerability stems from corals’ narrow temperature tolerance range. This makes them early indicators of climate change impacts.

Ocean acidification compounds temperature effects. Oceans absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide. This makes seawater more acidic. It reduces carbonate ion availability. These ions are essential for calcifying organisms like corals to build their skeletons. The process weakens reef structures. It inhibits coral growth and recovery (Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2017). Models project that under high-emission scenarios, 92% of global coral cover could disappear by 2100. This would be because of the combined effects of warming and acidification (Speers et al. 2016).

The implications extend far beyond corals themselves. Reef ecosystems host approximately 25% of all marine species. They cover less than 1% of the ocean floor. This makes their decline catastrophic for marine biodiversity (IFAW 2024). The economic consequences are equally severe. Reef fisheries support hundreds of millions of people worldwide (Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2017).

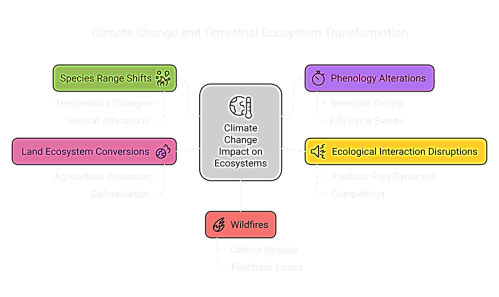

Terrestrial Ecosystem Transformation

Land ecosystems undergo equally profound transformations. Climate change drives shifts in species ranges. It alters phenology (timing of life cycle events). It disrupts ecological interactions. Plant communities covering almost half of Earth’s land surface will change composition significantly by 2100. 40% of land-based ecosystems will convert from one type to another (NASA 2014).

Research reveals regional climate effects magnify other drivers of biodiversity decline. Regional drying makes previously remote areas of tropical rainforest accessible. This increases hunting, logging, and conversion pressures. Warming expands cultivation zones for cold-intolerant crops upward in elevation. This threatens montane forests with agricultural conversion (Brodie & Watson 2023). These interactions mean climate change’s impacts typically exceed what would be expected from temperature increases alone.

Wildfires exemplify these compound effects. Fire frequency and intensity increase with warming and drying trends. This affects approximately four million square kilometers of Earth’s land annually. In 2021 alone, wildfires globally released about 1.76 billion tons of carbon. This created a dangerous feedback loop. Climate-driven fires release carbon. This further accelerates climate change (Kumar 2022).

Implications for Human Well-being

The biosphere’s decline severely threatens human well-being. It diminishes ecosystem services. Natural ecosystems provide food, water filtration, flood control, pollination, and climate regulation services. These are valued at trillions of dollars annually. Over half of global GDP depends directly on nature. More than a billion people rely on forests for their livelihoods (United Nations 2025).

The economic impacts of coral reef decline illustrate this relationship. Models estimate that avoiding the equivalent of 2.5 W m⁻² of radiative forcing could preserve $14-20 billion in consumer surplus from reef-associated fisheries through 2100. This is the difference between moderate and high emission scenarios (Speers et al. 2016). These figures exclude tourism, coastal protection, and other reef-associated services. This suggests total economic benefits of conservation exceed these estimates.

Indigenous communities and traditional societies face disproportionate impacts from biosphere decline. Many depend directly on intact ecosystems for cultural practices. They rely on them for traditional foods and medicines. Climate-driven ecosystem changes threaten these relationships. This creates not just economic hardship, but cultural loss as well (McElwee et al. 2023).

Food security represents another critical concern. Climate change threatens agricultural production directly. It alters temperature and precipitation patterns. It also reduces wild food sources from both terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Global population continues to grow. Maintaining sufficient food production amid declining ecosystem services creates significant challenges (Bolster et al. 2023).

Scientific Uncertainties and Research Priorities

Despite extensive research, significant knowledge gaps persist regarding biosphere decline. Most biodiversity loss projections rely on simplified models. These may not fully capture complex ecological interactions. Estimates vary depending on methodologies. They also vary by taxonomic groups, metrics, spatial scales, and time periods considered (Bellard et al. 2012).

Coral reef projections exemplify these uncertainties. IPCC assessments consistently predict severe reef declines. These conclusions stem primarily from a specific subset of models. They apply similar “excess heat” threshold methodologies. A systematic review of 79 studies projecting coral reef responses found five main modeling approaches. “Excess heat” models made up just one-third of studies. Yet they received a disproportionate 68% of citations (Kwiatkowski et al. 2024). This suggests potential methodological biases in mainstream climate impact assessments.

Research priorities include a better understanding of ecological tipping points and resilience factors. Recent studies highlight the need for long-term ecological monitoring. This would detect early warning signs of ecosystem collapse. It would also identify natural resilience mechanisms (Seddon et al. 2019). Such monitoring has already revealed important insights about biosphere carbon sinks. These help slow climate change. However, maintaining consistent funding for these “ecological weather stations” proves challenging. Short-term funding cycles create obstacles.

Improving models of species’ adaptive capacity represents another crucial research area. Most extinction risk assessments assume species’ environmental tolerances remain fixed. However, many organisms possess some capacity for genetic adaptation. They can make behavioral changes. They show phenotypic plasticity. Understanding these adaptive mechanisms could refine biodiversity loss projections. It could inform conservation strategies (Thomas 2019).

Conservation and Policy Responses

Addressing biosphere decline requires coordinated conservation approaches. These must recognize the interconnected nature of climate and biodiversity crises. Traditional protected area strategies remain important. But they must evolve to account for shifting species ranges and changing ecosystems. Climate-ready marine protected areas incorporate connectivity across temperature gradients. They protect potential climate refugia. These are areas where conditions may remain suitable for vulnerable species (Harvey et al. 2018).

Ecosystem-based adaptation strategies gain increasing attention. They can address both climate change and biodiversity goals simultaneously. Restoring mangroves sequesters carbon. It provides habitat for marine species. It protects coastlines from storm surges intensified by climate change. Such nature-based solutions offer cost-effective approaches to climate resilience. They support biodiversity at the same time (Seddon et al. 2019).

Novel conservation approaches also emerge in response to accelerating threats. Human-assisted evolution represents one controversial frontier. This involves selective breeding or genetic modification of organisms like corals. It aims to enhance their climate resilience. Advocates argue such interventions may prove necessary to preserve ecosystem functions amid rapid change. Critics caution about potential unintended consequences for ecosystem dynamics (van Oppen et al. 2015).

Policy momentum builds through international frameworks. The Global Biodiversity Framework was adopted at COP15 in December 2022. This landmark agreement established 23 targets focused on reducing threats to biodiversity. They include designating 30% of Earth’s land and oceans as protected areas by 2030 (Statista 2024). Progress toward these targets was reviewed at COP16 in Colombia in 2024. This established the Cali Fund. It aims to mobilize new funding streams for biodiversity action worldwide.

Future Scenarios and Adaptive Responses

Future biosphere trajectories depend on climate mitigation efforts and adaptation strategies. Under business-as-usual emissions scenarios, projections show climate change driving massive change. Nearly half of Earth’s terrestrial ecosystems could transform by 2100 (NASA 2014). However, ambitious emission reductions could reduce these impacts. They cannot eliminate them entirely.

Adaptive governance approaches gain traction as promising frameworks for managing uncertainty. Traditional management plans are static. Adaptive governance incorporates learning processes. It values stakeholder participation. It enables flexible responses to emerging challenges. This approach recognizes the social and institutional dimensions of ecosystem management. It considers these alongside ecological concerns (Harvey et al. 2018).

Conservation priorities increasingly focus on maintaining ecosystem functions and services. This shift moves away from preserving historical ecosystem states. It acknowledges that some ecosystem transformation is inevitable. Committed warming makes this unavoidable. Functional resilience becomes more achievable than compositional stability (Thomas 2019).

The economic case for action strengthens as valuation methods improve. Annual investments needed for biodiversity conservation by 2030 total approximately $200 billion. This is according to the Cali Fund target. It represents a substantial sum. Yet, it is modest compared to the estimated value of ecosystem services at risk (United Nations 2025). Progress toward mobilizing these resources accelerated with the launch of the Cali Fund in February 2025. It received contributions from private sector entities. These are companies commercially using genetic resources data.

Conclusion

Climate change drives unprecedented biosphere decline through multiple interacting mechanisms. It threatens to become the primary driver of biodiversity loss by mid-century. The consequences extend far beyond species extinctions. They encompass fundamental changes in ecosystem functioning. This has profound implications for human well-being. Scientific uncertainties remain. Yet the direction and severity of these trends appear consistent across diverse research approaches.

Effectively addressing this crisis requires integrated approaches. These must recognize the feedback mechanisms connecting climate change and biodiversity loss. Conservation strategies must evolve beyond traditional protected area approaches. They need to incorporate climate resilience, connectivity, and ecosystem functionality. Climate policy must expand beyond carbon accounting. It should consider biodiversity implications of different mitigation and adaptation pathways.

The next decade proves critical for determining future biosphere trajectories. Some ecosystem transformation appears inevitable. Committed warming makes this unavoidable. However, ambitious climate action could reduce the severity of biodiversity decline. Strategic conservation investments could help maintain critical ecosystem functions. This remains true even as compositions change. The challenge requires unprecedented cooperation. It must span scientific disciplines, policy domains, and national boundaries. The alternative of continued biosphere degradation carries unacceptable costs. Both natural systems and human societies would suffer.

References

Beaugrand G, Edwards M, Legendre L. 2010. Marine biodiversity, ecosystem functioning, and carbon cycles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107(22):10120-10124.

Bellard C, Bertelsmeier C, Leadley P, Thuiller W, Courchamp F. 2012. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecology Letters. 15(4):365-377.

Bolster CH, et al. 2023. Agriculture, food systems, and rural communities. In: Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA.

Bopp L, Resplandy L, Orr JC, Doney SC, Dunne JP, Gehlen M, Vichi M. 2013. Multiple stressors of ocean ecosystems in the 21st century: projections with CMIP5 models. Biogeosciences. 10:6225-6245.

Brodie JF, Watson JEM. 2023. Human responses to climate change will likely determine the fate of biodiversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 120(8).

Great Barrier Reef Foundation. 2024. Climate change. [accessed 2025 Feb 8]. https://www.barrierreef.org/the-reef/threats/climate-change.

Harvey CA, Chacón M, Donatti CI, Garen E, Hannah L, Andrade A, Wollenberg E, Brauman K, Schroth G. 2018. Climate change impacts and adaptation among smallholder farmers in Central America. Agriculture & Food Security. 7(1):1-20.

Hoegh-Guldberg O, et al. 2017. Coral reef ecosystems under climate change and ocean acidification. Frontiers in Marine Science. 4:158.

IFAW (International Fund for Animal Welfare). 2024. How climate change impacts the ocean. [accessed 2024 May 28]. https://www.ifaw.org/au/journal/climate-change-impact-ocean.

Kumar A. 2022. Climate change and its impact on biodiversity and human welfare. Current Science. 123(4):544-553.

Kwiatkowski L, et al. 2024. Systematic review of the uncertainty of coral reef futures under climate change. Nature Communications. 15:3141.

Malhi Y, et al. 2020. Potential feedbacks between loss of biosphere integrity and climate change. Global Sustainability. 3.

McElwee PD, et al. 2023. Ecosystems, ecosystem services, and biodiversity. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC.

NASA. 2014. Climate change may bring big ecosystem changes. [accessed 2014 Sep 16]. https://climate.nasa.gov/news/645/climate-change-may-bring-big-ecosystem-changes/.

NOAA. 2024. How does climate change affect coral reefs? [accessed 2025 Feb 8]. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/coralreef-climate.html.

Pereira HM, et al. 2024. Global trends and scenarios for terrestrial biodiversity and ecosystem services from 1900-2050. Science. [accessed 2025 Feb 8]. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/04/240425161518.htm.

Potapov P, et al. 2021. Changes in global cropland area 2003-2019. Earth System Science Data. 13:306-319.

Science Feedback. 2024. From vibrant corals to white skeletons: climate change and looming existential threats to coral reefs. [accessed 2025 Feb 8]. https://science.feedback.org/vibrant-corals-white-skeletons-climate-change-looming-existential-threats-coral-reefs/.

Seddon N, Chausson A, Berry P, Girardin CA, Smith A, Turner B. 2019. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 375(1794):20190120.

Speers AE, Besedin EY, Palardy JE, Moore C. 2016. Impacts of climate change and ocean acidification on coral reef fisheries: an integrated ecological-economic model. Environmental Research Letters. 11(11):114031.

Statista. 2024. Biodiversity loss – statistics & facts. [accessed 2025 Feb 8]. https://www.statista.com/topics/11263/biodiversity-loss/.

Thomas CD. 2019. The development of Anthropocene biotas. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 374(1763):20190113.

United Nations. 2025. Biodiversity – our strongest natural defense against climate change. [accessed 2025 Feb 8]. https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/climate-issues/biodiversity.

van Oppen MJH, Oliver JK, Putnam HM, Gates RD. 2015. Building coral reef resilience through assisted evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112(8):2307-2313.

Latest Posts: