How Can We Love What We Destroy?

A man stops traffic to carry a turtle across the road. A woman spends her savings rehabilitating injured raptors. Children organize to save species they will never encounter in the wild.

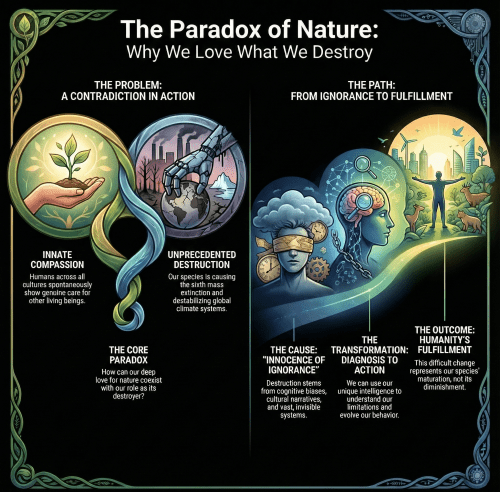

These acts of compassion are not rare. They appear everywhere, spontaneously, across cultures. Something in us responds to other living beings with genuine care.

Yet our species is dismantling the biosphere with unprecedented speed. We are driving what scientists call the sixth mass extinction. We are altering climate systems that took millions of years to stabilize. We are simplifying ecosystems beyond the point at which they could recover their former complexity.

How do these two realities coexist in the same creature?

I have spent several years exploring this question, drawing on peer-reviewed research in biological conservation, evolutionary psychology, cognitive science, and environmental science. The result is a nine-part essay series called The Innocence of Ignorance.

The series argues that most humans bear no malicious intent toward nature. Our destruction flows from ignorance, but not simple ignorance. It is ignorance maintained by cognitive biases shaped for ancestral societies and environments, by cultural narratives celebrating dominance, and by systems too vast to see from within.

The essays trace a path from diagnosis to transformation. They examine why our intelligence became dangerous, what thermodynamic and ecological realities constrain our choices, and what it would mean to mature from planetary destroyer to plain member and citizen of Earth’s community.

The essays are not a counsel of despair. Humans possess something unique: the capacity to understand our own limitations and consciously evolve our behavior. The transformation soon to be forced upon us will be difficult. It will be painful. But it represents not humanity’s diminishment, it represents our fulfillment.

The series builds on insights developed in my Earth in Transition books, but each essay stands alone.

[Read the Innocence of Ignorance series introduction and access all nine essays here.]