Fifty Years of Irreversible Change

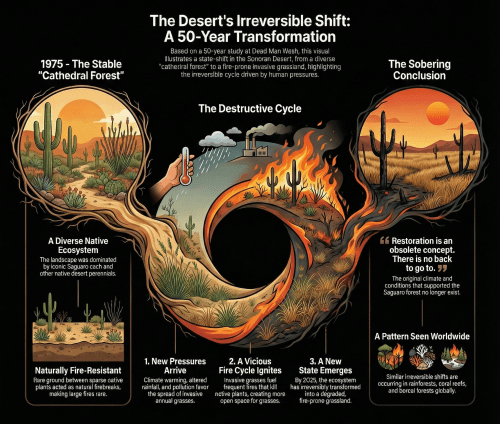

Theories and models can be dismissed as speculation. Long-term empirical data cannot. Rogers’ fifty-year longitudinal study in the Sonoran Desert provides concrete evidence for claims made in previous essays: that human impacts trigger irreversible state-shifts, that complexity built on temporary abundance collapses when that abundance ends, and that “restoration is an obsolete concept. There is no back to go to” (Rogers 2025, p. 10).

The data comes from Dead Man Wash, a site in the Sonoran Desert Rogers monitored from 1975 to 2025. What the observations reveal is not recovery but transformation, a case study in how ecosystems cross thresholds beyond which return becomes impossible.

The Baseline: A Cathedral Forest

In 1975, Dead Man Wash contained what Rogers terms a “cathedral forest” of Saguaro cacti (Rogers 2025, p. 13). These iconic giants, some reaching 15 meters tall and 200 years old, dominated the landscape. Beneath them grew diverse native perennials: palo verde trees, ironwood, creosote bush, brittlebush, and many other species adapted to arid conditions over millions of years.

This ecosystem represented classic Sonoran Desert vegetation—sparse by rainforest standards but rich in endemic species evolved for extreme heat, unpredictable rainfall, and intense solar radiation. The Saguaros served as keystone structures, providing nesting sites for birds, shelter for reptiles and mammals, and food resources through their flowers and fruit (McAuliffe 2007).

The ecosystem had persisted through previous droughts and fires. Saguaros, despite their size, are fire-sensitive, but historically fires were rare. Native desert vegetation does not create continuous fuel beds. Bare ground separates plants, preventing fire spread. The occasional lightning strike might kill individual plants but could not sustain landscape-scale burning (McLaughlin and Bowers 2002).

The Transformation Begins

Between 1975 and 2025, Rogers documented systematic changes. Climate warming altered precipitation patterns. Extended droughts became more frequent. When rain came, it fell in more intense pulses, running off rather than infiltrating (Rogers 2025, p. 13). Simultaneously, atmospheric nitrogen deposition from fossil fuel combustion and agricultural runoff increased across the Southwest—a subsidy favoring fast-growing annual plants over slow-growing natives (Rao and Allen 2010).

Invasive annual grasses, primarily buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare), red brome (Bromus rubens), and Mediterranean grass (Schismus barbatus), established and spread. Unlike native plants, these species form continuous carpets of vegetation during favorable years. When dry season arrives, they die back, creating continuous fuel beds connecting previously isolated plants (Brooks et al. 2004).

Fire frequency increased. What historically occurred once per century began happening every few decades, then every decade. Each fire killed fire-sensitive natives including Saguaros, palo verde, and ironwood. The invasive grasses, however, evolved in fire-prone Mediterranean and African ecosystems. They resprout quickly from surviving roots and seeds (D’Antonio and Vitousek 1992).

The Feedback Loop

Rogers observed a classic positive feedback loop (Rogers 2025, p. 13):

More invasive grass → More continuous fuel → More frequent fire → More native mortality → More open ground → More grass invasion → More fuel → More fire

Each iteration shifted the ecosystem further from its historical state. The Saguaros could not regenerate. New seedlings require nurse plants—larger shrubs or trees providing shade and protection during vulnerable early years (McAuliffe 1984). But the fires killed the nurse plants. Without them, Saguaro recruitment ceased.

This exemplifies what ecologists call a “state-shift” or “regime shift”—when an ecosystem crosses a threshold and reorganizes around a new stable state (Scheffer et al. 2001). The Sonoran Desert ecosystem proved bistable, existing in either a native perennial state or an invasive annual state. Fire pushed it from one basin of attraction to another.

Importantly, Rogers emphasizes native perennials displayed “weak or nonexistent recovery mechanisms. They did not bounce back; they vanished” (Rogers 2025, p. 13). This challenges conventional restoration ecology’s assumption that removing disturbance allows ecosystems to recover. Some changes prove irreversible on timescales relevant to human civilization.

The Current State

By 2025, Dead Man Wash had completed its transformation. The cathedral forest exists only in photographs and memories. Native perennials persist as scattered remnants. Invasive annual grasses dominate. Fire frequency remains high. The ecosystem has stabilized—but in a degraded state delivering fewer ecosystem services and supporting reduced biodiversity.

To a visitor encountering the site for the first time, the weedy landscape appears normal. This illustrates “shifting baseline syndrome”—each generation accepts degraded conditions as natural (Pauly 1995; Papworth et al. 2009). Without long-term monitoring data, the transformation remains invisible. The memory of the cathedral forest has been erased.

Rogers notes that “the data from Dead Man Wash is not an anomaly; it is a fractal of the planetary condition” (Rogers 2025, p. 13). Similar patterns appear across major biomes:

- Amazonian rainforest experiencing savannization as drought and fire increase (Brando et al. 2020)

- Coral reefs shifting from coral to algal dominance following bleaching events (Hughes et al. 2017)

- Boreal forests burning faster than they can regrow, transitioning to grassland (Johnstone et al. 2010)

- Arctic tundra converting to shrubland as warming accelerates (Myers-Smith et al. 2011)

Each represents a state-shift driven by climate change, creating positive feedbacks preventing return to previous conditions.

Thermodynamic Interpretation

The Sonoran Desert data illustrates principles from our previous essay on thermodynamics. The native ecosystem represented a configuration adapted to the region’s historical energy budget: Solar input, seasonal rainfall patterns, nutrient availability. This configuration persisted for millennia.

Fossil fuel combustion altered that energy budget. Warmer temperatures increased evapotranspiration. Changed precipitation patterns reduced water availability. Nitrogen deposition provided thermodynamic subsidy to fast-growing species. Together, these changes made the historical configuration thermodynamically unstable.

The ecosystem reorganized to a new configuration matching altered energy flows. The invasive grass-fire regime proves stable under current conditions but delivers reduced complexity and ecosystem services. As Rogers states, this represents “Saguaro civilization in a drought/fire environment,” complexity built on temporary conditions becoming impossible when those conditions change (Rogers 2025, p. 18).

Implications for Restoration

The Sonoran Desert data carries profound implications for ecological restoration. Traditional restoration assumes removing disturbance allows ecosystems to recover through natural succession. But when state-shifts occur, removing disturbance proves insufficient.

Even if we could eliminate invasive grasses and prevent fire, the climate has changed. The precipitation patterns favoring Saguaro recruitment no longer exist. The temperature regime exceeds physiological tolerances. The ecosystem cannot return to its 1975 state because the thermodynamic conditions supporting that state no longer exist.

This supports Rogers’ stark conclusion: “Restoration is an obsolete concept. There is no back to go to” (Rogers 2025, p. 10). We can manage current conditions, facilitate adaptation to new conditions, or assist transition to novel ecosystems. But we cannot restore what was.

This challenges conservation biology’s traditional goal of maintaining historical conditions. As ecologist Richard Hobbs argues, we must embrace “novel ecosystems,” combinations of species and conditions without historical precedent (Hobbs et al. 2009). Some preserve ecosystem function if not composition. Others represent degraded states requiring active management.

The Pattern Repeats

Rogers emphasizes that Dead Man Wash exemplifies patterns visible globally (Rogers 2025, p. 14). Across every major biome, human activities push ecosystems past thresholds. The specific mechanisms vary, drought, fire, nutrients, invasive species, overharvesting, but the outcome repeats: irreversible transformation to degraded states.

The data contradicts optimistic narratives of ecosystem resilience. While ecosystems can absorb some disturbance, there are limits. Cross those limits and systems reorganize. The new states often persist even when disturbance ceases.

This connects to our earlier essays on pathological adolescence. Adolescents believe they are invincible, that consequences can always be reversed. The empirical data from fifty years of monitoring says otherwise. Some damage proves permanent. Some thresholds, once crossed, cannot be recrossed. Some complexity, once lost, cannot be recovered.

The Sonoran Desert teaches what the adolescent refuses to learn: actions have consequences, systems have limits, and some changes cannot be undone. The question becomes whether humanity will accept this lesson voluntarily or require catastrophe to drive it home—the subject of our next essay.

References

Brando, P. M., Paolucci, L., Ummenhofer, C. C., Ordway, E. M., Hartmann, H., Cattau, M. E., … & Balch, J. K. (2020). Droughts, wildfires, and forest carbon cycling: A pantropical synthesis. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 48, 555-581.

Brooks, M. L., D’Antonio, C. M., Richardson, D. M., Grace, J. B., Keeley, J. E., DiTomaso, J. M., … & Pyke, D. (2004). Effects of invasive alien plants on fire regimes. BioScience, 54(7), 677-688.

D’Antonio, C. M., & Vitousek, P. M. (1992). Biological invasions by exotic grasses, the grass/fire cycle, and global change. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 23(1), 63-87.

Hobbs, R. J., Higgs, E., & Harris, J. A. (2009). Novel ecosystems: Implications for conservation and restoration. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 24(11), 599-605.

Hughes, T. P., Barnes, M. L., Bellwood, D. R., Cinner, J. E., Cumming, G. S., Jackson, J. B., … & Scheffer, M. (2017). Coral reefs in the Anthropocene. Nature, 546(7656), 82-90.

Johnstone, J. F., Hollingsworth, T. N., Chapin, F. S., & Mack, M. C. (2010). Changes in fire regime break the legacy lock on successional trajectories in Alaskan boreal forest. Global Change Biology, 16(4), 1281-1295.

McAuliffe, J. R. (1984). Sahuaro-nurse tree associations in the Sonoran Desert: competitive effects of sahuaros. Oecologia, 64(3), 319-321.

McAuliffe, J. R. (2007). Desert soils. In The Sonoran Desert: Origin and Prospects (pp. 87-104). University of Arizona Press.

McLaughlin, S. P., & Bowers, J. E. (2002). Effects of wildfire on a Sonoran Desert plant community. Ecology, 83(11), 3024-3040.

Myers-Smith, I. H., Forbes, B. C., Wilmking, M., Hallinger, M., Lantz, T., Blok, D., … & Hik, D. S. (2011). Shrub expansion in tundra ecosystems: Dynamics, impacts and research priorities. Environmental Research Letters, 6(4), 045509.

Papworth, S. K., Rist, J., Coad, L., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2009). Evidence for shifting baseline syndrome in conservation. Conservation Letters, 2(2), 93-100.

Pauly, D. (1995). Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 10(10), 430.

Rao, L. E., & Allen, E. B. (2010). Combined effects of precipitation and nitrogen deposition on native and invasive winter annual production in California deserts. Oecologia, 162(4), 1035-1046.

Rogers, G. (2025). Manifesto of the Initiation. Coldwater Press.

Scheffer, M., Carpenter, S., Foley, J. A., Folke, C., & Walker, B. (2001). Catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Nature, 413(6856), 591-596.

[Read the series introduction and access all nine essays here.]