The Involuntary Path to Maturity

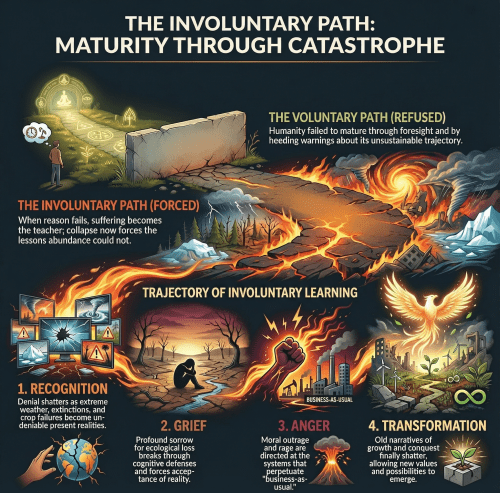

We have established universal cognition, diagnosed pathological adolescence, examined thermodynamic constraints, and documented irreversible ecological transformation. The pattern is clear: industrial civilization’s current trajectory proves unsustainable. The question becomes: How does transformation occur? Rogers offers a sobering answer: “Because we refused to mature voluntarily through foresight, we must now mature involuntarily through catastrophe” (Rogers 2025, p. 9).

The floods, fires, famines, and extinctions are not random disasters but “initiatory ordeals required to shatter our industrial ego.” Suffering becomes teacher when reason fails. Loss instructs where abundance taught nothing. This is the unwelcome pedagogy of collapse.

The Psychology of Crisis Learning

Developmental psychology reveals that adolescents often require painful experiences to accept realities they have intellectually rejected. Warnings prove insufficient. The crash teaches what caution could not. The hangover instructs where moderation failed. The lost relationship shows what arguments could not convey.

This pattern extends to cultures. Historian Arnold Toynbee argued civilizations grow by responding to challenges but collapse when responses become inadequate (Toynbee 1946). The successful response to one challenge often creates conditions for the next crisis. What worked before no longer works. Adaptation requires abandoning previously successful strategies.

Psychologist Jean Piaget termed this process “accommodation”—when new experiences cannot be assimilated into existing mental frameworks, the frameworks themselves must change (Piaget 1954). This proves cognitively painful. People resist accommodation, preferring assimilation—distorting new information to fit existing beliefs. Only when distortion becomes impossible does accommodation occur.

At civilizational scale, accommodation requires abandoning core narratives: progress through conquest, nature as resource, growth as imperative, technology as salvation. These narratives structure collective identity. Releasing them feels like psychological death. Only suffering powerful enough to shatter the frameworks forces transformation.

Ecological Grief as Catalyst

Philosopher Glen Albrecht coined “solastalgia” to describe distress caused by environmental change (Albrecht et al. 2007). Unlike nostalgia, longing for distant places or times, solastalgia emerges from transformation of familiar environments. Home becomes unfamiliar. The landscape you love no longer exists.

This grief is intensifying. Climate scientists report psychological distress from witnessing planetary degradation (Cunsolo and Ellis 2018). Farmers mourn disappearing seasons and crops. Indigenous communities grieve extinctions of culturally significant species. Children express anxiety regarding futures they feel have been stolen (Hickman et al. 2021).

Rogers argues that this grief serves essential function: it breaks through cognitive barriers preventing recognition of reality (Rogers 2025g). Optimism bias, shifting baselines, and strategic ignorance (discussed in earlier essays) insulate consciousness from environmental truth. Direct experience of loss penetrates these defenses.

Research confirms this mechanism. Studies show that direct experience of environmental change proves more effective than abstract information in shifting perceptions and motivating behavior (Spence et al. 2011). The flood that destroys your home teaches more than climate models. The drought that kills your crops instructs more than reports. The species extinction you witness transforms more than statistics.

This creates tragic irony. The cognitive biases preventing voluntary transformation ensure transformation will come through suffering. The adolescent who refuses to learn from warnings must learn from consequences.

The Trajectory of Involuntary Learning

Rogers describes the “avalanche of biosphere collapse has begun” (Rogers 2025, p. 6). What does involuntary learning through catastrophe look like at planetary scale?

First comes recognition when carefully constructed narratives maintaining collective denial fracture. Extreme weather events become undeniable. Species extinctions accelerate beyond background noise. Crop failures trigger food insecurity. These are not distant future scenarios but present realities penetrating consciousness.

Next comes grief. As Joanna Macy documents, acknowledging ecological devastation generates profound sorrow—what she terms “the work that reconnects” (Macy and Johnstone 2012). This grief is not depression but appropriate response to genuine loss. It signals the attachment being severed and the reality being faced.

Then comes anger. Systems maintaining business-as-usual despite mounting evidence of catastrophe generate rage. Intergenerational injustice—older generations enjoying abundance while leaving younger ones with collapse—creates moral outrage. This anger can become destructive or catalytic depending on how it is channeled.

Finally comes transformation. When denial, bargaining, and rage exhaust themselves, accommodation becomes possible. The old frameworks shatter. New understanding emerges. Different values crystallize. Alternative possibilities become visible.

Historical Parallels

This pattern repeats throughout human history. The Black Death shattered medieval European society but catalyzed social transformations including weakening feudalism and spurring scientific inquiry (Herlihy 1997). World War II’s devastation prompted United Nations creation and human rights codification. The 1970s oil crises triggered energy efficiency improvements and renewable energy research.

Catastrophe creates what sociologists call “windows of opportunity,” moments when normal constraints loosen and systemic change becomes possible (Kingdon 1984). Crisis delegitimizes failing systems. Emergency mobilization proves feasible when normal politics would prevent it. Social cohesion increases through shared suffering.

Yet catastrophe does not guarantee positive transformation. It can also catalyze authoritarianism, scapegoating, and collapse without recovery. The Roman Empire’s fall led to centuries of reduced complexity. Many civilizations disappeared entirely, leaving only archaeological traces (Tainter 1988).

The difference lies in whether sufficient “cultural and genetic seeds” survive to enable regeneration (Rogers 2025, p. 9). If collapse destroys knowledge, infrastructure, and social trust completely, recovery becomes impossible. This underlies the urgency of preserving both biological diversity and cultural wisdom.

The Accelerating Cascade

Current trajectories suggest involuntary learning will intensify. Climate impacts are accelerating. Biodiversity loss continues. Soil degradation advances. Ocean acidification proceeds. Each represents a teacher administering increasingly harsh lessons.

The thermodynamic constraints discussed in Essay 4 ensure this acceleration. As fossil fuel EROI declines and climate damages mount, maintaining current complexity becomes costlier. System stress increases. Failures multiply. Cascading crises replace isolated events.

Rogers notes ecosystems are crossing thresholds into degraded states from which recovery proves impossible (Rogers 2025, p. 13). The Sonoran Desert case study in Essay 5 exemplifies this pattern. Each threshold crossed makes subsequent thresholds more likely and positive feedbacks generate runaway change.

This creates what researchers term “synchronous failures”—when multiple systems fail simultaneously, overwhelming adaptive capacity (Homer-Dixon et al. 2015). Financial crisis plus drought plus pandemic plus political instability exceeds society’s ability to respond. The teachers arrive faster than lessons can be integrated.

The Ethics of Suffering

Is suffering-as-teacher morally acceptable? Rogers acknowledges the tragedy: innocent beings, human and nonhuman, will suffer for failures they did not cause (Rogers 2025, p. 9). Children born today inherit catastrophe they had no role in creating. Countless species face extinction because of human choices made before they evolved.

This raises profound questions of intergenerational and interspecies justice. Traditional ethics struggles with harms spanning generations and species boundaries. Yet these are precisely the scales at which ecological catastrophe operates.

Some argue suffering is unnecessary—that voluntary transformation remains possible through education, policy reform, and technological innovation. Others contend that the depth of transformation required exceeds what voluntary change can achieve. Only crisis shatters frameworks deeply enough to enable fundamental reorientation.

The uncomfortable truth may be that both are correct. Voluntary transformation is possible but improbable given cognitive biases and institutional inertia. Involuntary transformation through suffering is probable but not guaranteed to be constructive. The window for choosing the path is closing.

Learning from Suffering Wisely

If suffering is inevitable, can we at least ensure it teaches effectively? Several principles emerge:

- First, witness and remember. Document what is being lost. Record ecosystem transformations, species extinctions, cultural disintegration. Long-term ecological monitoring like Rogers’ Sonoran Desert study provides essential perspective. Without this memory, shifting baselines erase the lessons.

- Second, grieve fully. Suppressing ecological grief prevents the accommodation necessary for transformation. As Macy argues, honoring loss creates space for new understanding (Macy and Johnstone 2012).

- Third, maintain seeds. Preserve biological diversity, practical knowledge, and institutional capacity to enable regeneration. Not everything can be saved, but what survives determines what becomes possible afterward.

- Fourth, channel anger constructively. Rage at systems perpetuating collapse can energize transformation or devolve into destructive scapegoating. The difference lies in directing anger toward systemic change rather than interpersonal violence.

- Fifth, cultivate cognitive adaptation, our next essay’s focus. The involuntary path teaches through suffering, but humans possess unique capacity to learn from others’ suffering, anticipate futures, and consciously evolve culture. We need not experience every catastrophe personally to transform.

The Bitter Necessity

Rogers terms the current crisis an “Initiation”—the painful rite of passage from adolescence to maturity (Rogers 2025, p. 12). Initiations in traditional cultures involve ordeals precisely because transformation requires shattering old identity. The pain isn’t punishment but necessary catalyst.

At civilizational scale, the initiation involves witnessing and grieving biosphere degradation, accepting limits previously denied, releasing narratives of human dominance, and emerging with different consciousness. This is “the necessary price of admission to the next stage of life, a true enlightenment” (Rogers 2025, p. 12).

The tragedy is that it need not have been involuntary. Had industrial civilization matured voluntarily through foresight, much suffering could have been prevented. But the adolescent refused. The warnings were dismissed. The opportunities were squandered. Now the teachers arrive uninvited, bearing lessons no one wanted to learn.

The question is whether humanity can learn quickly enough whether the transformation can occur before collapse becomes irreversible. That depends on the final adaptation—the conscious evolution of human cognition and culture, which we explore next.

References

Albrecht, G., Sartore, G. M., Connor, L., Higginbotham, N., Freeman, S., Kelly, B., … & Pollard, G. (2007). Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. Australasian Psychiatry, 15(sup1), S95-S98.

Cunsolo, A., & Ellis, N. R. (2018). Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nature Climate Change, 8(4), 275-281.

Herlihy, D. (1997). The Black Death and the Transformation of the West. Harvard University Press.

Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R. E., Mayall, E. E., … & van Susteren, L. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs regarding government responses to climate change. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(12), e863-e873.

Homer-Dixon, T., Walker, B., Biggs, R., Crépin, A. S., Folke, C., Lambin, E. F., … & Troell, M. (2015). Synchronous failure: The emerging causal architecture of global crisis. Ecology and Society, 20(3), 6.

Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Little, Brown.

Macy, J., & Johnstone, C. (2012). Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in Without Going Crazy. New World Library.

Piaget, J. (1954). The Construction of Reality in the Child. Basic Books.

Rogers, G. (2025). Manifesto of the Initiation. Coldwater Press.

Rogers, G. (2025g). The final adaptation—Evolving our minds for a wounded planet. GarryRogers Nature Conservation. https://garryrogers.com/2025/08/01/

Spence, A., Poortinga, W., Butler, C., & Pidgeon, N. F. (2011). Perceptions of climate change and willingness to save energy related to flood experience. Nature Climate Change, 1(1), 46-49.

Tainter, J. A. (1988). The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press.

Toynbee, A. J. (1946). A Study of History. Oxford University Press.

[Read the series introduction and access all nine essays here.]