When Intelligence Becomes Dangerous

In our first essay, we established that cognition pervades the biosphere. Humans are not uniquely thinking beings, but extraordinary elaborations of capacities found throughout life. This recognition raises a troubling question: If human cognition is continuous with nature, why have we become nature’s greatest threat? Why does our intelligence, which allows us to understand ecological relationships in unprecedented detail, simultaneously enable their destruction?

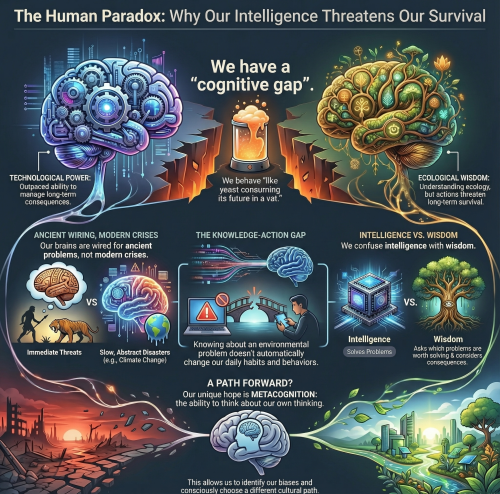

This as “The Human Paradox”. Human cognition represents an extraordinary elaboration of capacities found throughout the biosphere, “the same intelligence that allows us to understand the intricate workings of the biosphere has also given us the technology to disrupt it” (Rogers 2025f). We suffer from “a cognitive gap between our technological capacity and our ecological wisdom.”

This paradox manifests with devastating clarity in contemporary environmental crises. We are the only species capable of understanding the laws of physics governing our world, yet we behave, as Rogers notes, “like yeast consuming its future in a vat” (Rogers 2025, p. 6). We possess unprecedented knowledge of climate dynamics, biodiversity interdependencies, and ecosystem functions—yet current species extinction rates run three orders of magnitude higher than background rates (Tilman et al. 2022).

The Amplification of Cognitive Capacity

To understand this paradox, we must examine what makes human cognition distinct. Our capacity for symbolic language allows us to represent abstract concepts, communicate complex ideas, and build cumulative knowledge across generations. Cultural evolution has accelerated beyond biological evolution, allowing humans to adapt to new environments through learned behaviors rather than genetic changes (Boyd and Richerson 1985).

This cultural transmission creates what ecologists term the “extended phenotype”—human impacts extending far beyond individual bodies to reshape entire landscapes (Dawkins 1982). Agriculture, urbanization, industrialization—these represent cognitive elaborations manifesting as planetary-scale transformations. No other species has matched this capacity to reshape Earth systems through accumulated knowledge.

Yet this same capacity creates unprecedented risks. As Stoknes (2015) documents, humans excel at solving immediate, short-term problems. Our ancestors who quickly identified threats, found food, and built shelter survived. But addressing slow-moving, long-term crises like climate change requires cognitive capabilities we did not evolve to possess. The threats are too large, too diffuse, too delayed to trigger our inherited risk-assessment systems.

The Technological Trap

Technology amplifies this paradox. Human tool use, present throughout our evolutionary history, has accelerated through cultural transmission. Modern technology provides extraordinary power to extract resources, transform landscapes, and manipulate natural systems. Yet our capacity to predict and manage the consequences has not kept pace.

Consider fossil fuels. The thermodynamic leverage provided by concentrated ancient sunlight has enabled population growth, technological development, and material wealth unprecedented in human history. Yet this same energy source drives climate change, ocean acidification, and ecosystem disruption. We understood the greenhouse effect in the 1890s. We documented rising atmospheric carbon dioxide in the 1950s. We predicted warming’s consequences in the 1980s. Yet emissions continued rising (Oreskes and Conway 2010).

This isn’t stupidity. The intelligence required to discover fossil fuels, build global energy systems, and model climate dynamics is extraordinary. The paradox lies in deploying such intelligence to create systems whose full consequences we cannot, or will not, address.

Ellis and colleagues (2023) demonstrate that humans have shaped most terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years, from fire-stick farming to selective breeding to landscape modification. This long history of environmental manipulation created the Holocene’s relative stability. What has changed in recent centuries is the scale and pace of change. Industrial technology compressed millennia of environmental transformation into decades.

Cognitive Architecture Mismatched to Reality

The human paradox becomes clearer when we examine our cognitive architecture. Evolution shaped human minds for small-group hunter-gatherer existence, where threats were immediate, social relationships direct, and environmental feedback rapid (Cosmides and Tooby 1997). This heritage creates systematic biases when confronting planetary-scale multi-generational challenges.

We discount future consequences, valuing immediate rewards over long-term benefits—an adaptive trait when future survival was uncertain (Frederick et al. 2002). We respond more strongly to individual suffering than statistical abstractions. One identifiable victim triggers greater empathy than thousands of anonymous casualties (Slovic 2007). We maintain optimism about personal futures even when acknowledging general risks, a bias that once motivated perseverance but now prevents realistic risk assessment (Sharot 2011).

Rogers emphasizes that humanity is “hobbled by cognitive biases that were once adaptive but are now perilous,” including temporal discounting, excessive optimism regarding risk, and difficulty grasping “the slow, cascading nature of complex system collapse” (Rogers 2025g). These are not character flaws but universal features of human information processing.

The philosopher Timothy Morton (2013) terms climate change a “hyper object,” something so massively distributed in time and space that it defeats human comprehension. We can measure it, model it, document it. But we cannot perceive it directly. It exceeds the scale our cognition evolved to handle.

The Knowledge-Action Gap

Perhaps most troubling is what psychologists term the “knowledge-action gap”—knowing what should be done yet failing to act accordingly (Kollmuss and Agyeman 2002). Surveys consistently show high percentages of people expressing concern regarding environmental issues. Yet behavior changes lag far behind stated values.

This gap isn’t hypocrisy but reflects the complex relationship between explicit knowledge and implicit behavior. Evolutionary psychologists distinguish “System 1” thinking (fast, automatic, intuitive) from “System 2” thinking (slow, deliberate, analytical) (Kahneman 2011). Environmental awareness operates in System 2. Daily behaviors run on System 1. Changing System 1 requires more than intellectual understanding.

Research on environmental behavior reveals that knowledge alone rarely drives action. Emotional connection, social norms, personal efficacy, and structural enablers prove equally or more important (Steg and Vlek 2009). Understanding climate science does not automatically change consumption patterns. Knowing extinction rates does not transform land-use decisions.

Intelligence Without Wisdom

The human paradox is intelligence without wisdom. We possess extraordinary analytical capacity to understand ecological systems. We can model future scenarios, quantify risks, and identify solutions. Yet we lack the collective wisdom to align behavior with knowledge.

The distinction matters. Intelligence solves problems. Wisdom knows which problems to solve and what consequences matter. Intelligence created industrial civilization. Wisdom asks whether such civilization serves long-term flourishing. Intelligence builds powerful technologies. Wisdom questions whether we should build everything we can.

This lack of wisdom manifests in what Rogers diagnoses as “pathological industrial adolescence”—a condition we will explore in our next essay. The adolescent possesses adult intelligence and power but lacks mature judgment. The adolescent believes themselves invincible, focused on immediate gratification, rebelling against limits they do not yet understand they need.

The Promise Within the Paradox

Yet the human paradox contains potential. The same cognitive elaboration that created the crisis might enable solutions. We are “the only known species capable of understanding [our] own cognitive shortcomings, studying [our] history, anticipating distant futures, and consciously choosing to evolve [our] culture” (Rogers 2025g).

This metacognitive capacity, the ability to think regarding our thinking, distinguishes human cognition even among cognitively sophisticated species. We can identify our biases, design systems to counteract them, and deliberately cultivate different values. We can choose cultural evolution’s direction.

The question is whether we will exercise this capacity in time. As subsequent essays will explore, the obstacles are formidable: developmental immaturity, thermodynamic constraints, irreversible changes already set in motion, and the painful learning required when voluntary transformation proves insufficient.

But the possibility remains. Human intelligence created the paradox. Human wisdom might yet resolve it.

Read the series introduction and access the other essays.

References

Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (1985). Culture and the Evolutionary Process. University of Chicago Press.

Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (1997). Evolutionary psychology: A primer. Center for Evolutionary Psychology, University of California, Santa Barbara.

Dawkins, R. (1982). The Extended Phenotype. Oxford University Press.

Ellis, E. C., Gauthier, N., Klein Goldewijk, K., Bliege Bird, R., Boivin, N., Díaz, S., … & Watson, J. E. (2021). People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(29), e2218772120.

Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G., & O’Donoghue, T. (2002). Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 351-401.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Macmillan.

Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239-260.

Morton, T. (2013). Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. University of Minnesota Press.

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2010). Merchants of Doubt. Bloomsbury Press.

Rogers, G. (2025). Manifesto of the Initiation. Coldwater Press.

Rogers, G. (2025f). The human paradox—Our place in the cognitive web. GarryRogers Nature Conservation. https://garryrogers.com/2025/07/29/

Rogers, G. (2025g). The final adaptation—Evolving our minds for a wounded planet. GarryRogers Nature Conservation. https://garryrogers.com/2025/08/01/

Sharot, T. (2011). The optimism bias. Current Biology, 21(23), R941-R945.

Slovic, P. (2007). “If I look at the mass I will never act”: Psychic numbing and genocide. Judgment and Decision Making, 2(2), 79-95.

Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2009). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(3), 309-317.

Stoknes, P. E. (2015). What We Think Regarding When We Try Not to Think Regarding Global Warming. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Tilman, D., Clark, M., Williams, D. R., Kimmel, K., Polasky, S., & Packer, C. (2022). Future threats to biodiversity and pathways to their prevention. Nature, 546(7656), 73-81.