A Developmental Diagnosis

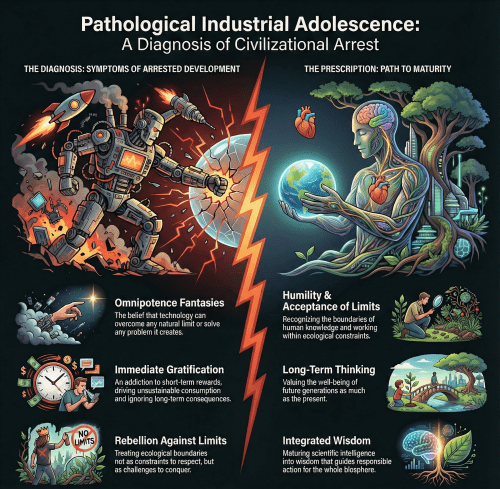

We have established that cognition pervades the biosphere and that human intelligence paradoxically enables both understanding and destruction of ecological systems. Now we must diagnose the specific condition afflicting industrial civilization. Rogers offers a provocative framework: humanity exhibits “pathological industrial adolescence” characterized by “omnipotence fantasies,” “immediate gratification,” and “rebellion against limits” (Rogers 2025, p. 8).

This is not metaphor but diagnosis. The adolescent brain possesses adult capacities for abstract reasoning and technological manipulation but lacks mature judgment, long-term planning, and acceptance of limits. The adolescent believes themselves invincible, resists external constraints, and focuses on immediate desires over long-term consequences. Sound familiar?

Omnipotence Fantasies

The first symptom of industrial adolescence is omnipotence fantasy—the belief that human technology can overcome any constraint. We will engineer our way out of climate change through carbon capture. We will replace depleted fisheries with aquaculture. We will substitute extinct species with synthetic biology. We will escape Earth’s limits by colonizing Mars.

These are not necessarily impossible ventures. The concerning pattern is faith in technological salvation without genuine reckoning with limits. As historian John McNeill (2001) documents, the 20th century witnessed unprecedented faith in human capacity to control nature. Massive engineering projects redirected rivers, drained wetlands, and reshaped coastlines with confidence that negative consequences could be managed.

The results have been mixed at best. The Aral Sea, once the world’s fourth-largest lake, shrank to 10% of its original size following irrigation diversion—creating an ecological and humanitarian disaster that no subsequent technology could reverse (Micklin 2007). The Three Gorges Dam in China generates enormous hydroelectric power but displaced over a million people and altered ecosystems along 600 kilometers of river (Stone 2011).

Geoengineering proposals to counteract climate change through stratospheric aerosol injection or ocean fertilization exemplify omnipotence thinking. Rather than reducing emissions, we imagine deliberately manipulating planetary systems we barely understand. As climate scientist Raymond Pierrehumbert notes, these schemes treat symptoms while ignoring causes—like treating lung cancer with painkillers while continuing to smoke (PierreHumbert 2015).

The psychological literature documents this pattern. Optimism bias leads individuals to believe they are less vulnerable to risks than others, even when objective evidence suggests equivalent exposure (Weinstein 1980). At civilizational scale, this manifests as techno-optimism—belief that innovation will solve problems created by previous innovations.

Immediate Gratification

The second symptom is addiction to immediate gratification. Industrial civilization runs on consumption—economic growth measured by how much we extract, produce, and discard. Quarterly earnings drive corporate decisions. Election cycles shape political priorities. Social media rewards instant engagement. The long-term becomes invisible.

Behavioral economics documents humans’ tendency toward temporal discounting, valuing immediate rewards far more than future benefits (Frederick et al. 2002). Offer someone $100 today or $110 next week, and many choose immediate payment. This made evolutionary sense when future survival was uncertain. But it proves catastrophic when applied to climate change, where preventing future damages requires immediate costs.

The fossil fuel economy epitomizes this pattern. We extract and burn concentrated energy accumulated over millions of years, enjoying unprecedented material abundance now while externalizing costs to future generations. As economist Nicholas Stern noted, climate change represents “the greatest market failure the world has seen” precisely because current actors reap benefits while future generations bear costs (Stern 2007).

Consumer culture reinforces immediate gratification through planned obsolescence, advertising stimulating desire for unnecessary products, and credit systems allowing consumption beyond means (Leonard 2010). The adolescent demands what they want now, dismissing concerns regarding future consequences as adult nagging.

Rebellion Against Limits

The third symptom is rebellion against limits. Industrial civilization treats ecological boundaries not as defining constraints but as challenges to overcome. Soil depletion? Apply more fertilizer. Water scarcity? Drill deeper wells. Species extinction? Create zoos and seed banks. Climate change? Develop air conditioning.

This rebellion manifests in what environmental scientists call “shifting baselines”—the gradual adjustment of expectations to accommodate degraded conditions (Pauly 1995). Each generation accepts the diminished environment they inherit as normal, making further deterioration seem acceptable. The adolescent refuses to acknowledge that rules apply to them.

Planetary boundaries research identifies nine critical Earth system processes where crossing thresholds could trigger abrupt or irreversible environmental changes (Rockström et al. 2009; Steffen et al. 2015). These include climate change, biosphere integrity, land-system change, freshwater use, biogeochemical flows, ocean acidification, and atmospheric aerosol loading. Current assessments suggest we have already crossed safe boundaries for climate, biosphere integrity, and biogeochemical flows.

Yet policy responses remain inadequate. International climate negotiations proceed as though physics might negotiate. Biodiversity conservation targets are set and missed repeatedly. Resource extraction accelerates despite mounting evidence of depletion. The mature adult accepts limits and works within them. The adolescent denies limits exist.

The Neurobiological Parallel

The adolescence metaphor extends to neurobiology. Brain imaging studies reveal that adolescent prefrontal cortex—responsible for long-term planning, risk assessment, and impulse control—continues developing into the mid-twenties (Giedd 2004). Adolescents possess advanced cognitive capacities but limited regulatory control. They understand consequences intellectually but struggle to apply this understanding to behavior.

Similarly, industrial civilization possesses extraordinary scientific knowledge regarding ecological systems but struggles to translate understanding into effective action. We model climate futures in exquisite detail yet increase emissions. We document extinction rates yet expand habitat destruction. We understand system dynamics yet promote policies prioritizing short-term growth over long-term stability.

Psychologist Daniel Goleman (2009) distinguishes between cognitive intelligence and emotional intelligence—the capacity to manage emotions, understand others, and make wise decisions. High cognitive intelligence does not guarantee emotional maturity. The brilliant adolescent can solve differential equations but throws tantrums when denied dessert.

Cultural Maturity Arrested

Why has industrial civilization remained arrested in adolescence? Several factors converge:

First, the fossil fuel subsidy created illusion of limitlessness. Concentrated ancient energy allowed temporary escape from ecological constraints, fostering belief that limits no longer apply. As Rogers notes in his thermodynamic critique (which we will explore in our next essay), industrial civilization represents “Saguaro civilization in a drought/fire environment,” complexity built on temporary abundance (Rogers 2025, p. 18).

Second, market economies externalize costs. Corporations profit from activities whose negative consequences fall on commons, future generations, or distant populations. This creates systematic incentive for immature behavior. The mature actor considers full consequences. The adolescent takes what they want and leaves cleanup to others.

Third, cultural narratives celebrate conquest over cooperation. The mythology of progress, manifest destiny, and human dominance shapes collective identity. Environmentalist Paul Shepard argued that industrial society suffers from “chronic juvenilization”—arrested development where adult responsibilities are avoided (Shepard 1998).

Fourth, education emphasizes technical skills over wisdom. We train specialists who understand narrow domains but lack integration across disciplines or consideration of broader contexts. As ecologist Aldo Leopold lamented, “We can be ethical only in relation to something we can see, feel, understand, love, or otherwise have faith in” (Leopold 1949, p. 251). Our education creates competent technicians but not mature citizens of the biosphere.

The Cost of Arrested Development

Developmental arrest carries consequences. Adolescents who cannot mature face restricted opportunities, damaged relationships, and mounting crises. At civilizational scale, arrested development manifests as ecological overshoot, climate disruption, mass extinction, and social breakdown.

Rogers argues that “because we refused to mature voluntarily through foresight, we must now mature involuntarily through catastrophe” (Rogers 2025, p. 9). The floods, fires, famines, and ecosystem collapses are not random disasters but “initiatory ordeals required to shatter our industrial ego.”

This suffering-as-teacher dynamic appears throughout developmental psychology. Adolescents often require painful experiences to accept realities they have intellectually rejected. The crash teaches what warnings could not. The loss instructs where abundance taught nothing.

The Path to Maturity

Yet maturity remains possible. Brain plasticity allows continued development throughout life. Cultural evolution can accelerate beyond biological timescales. The question is whether transformation occurs through voluntary growth or involuntary collapse.

Mature civilizations would display:

Humility regarding knowledge limits and capacity for control

Long-term thinking valuing future generations equally with present ones

Acceptance of constraints as defining boundaries rather than challenges to overcome

Integration of understanding across disciplines and scales

Reciprocity with systems providing life support

These represent not abandonment of intelligence but its maturation into wisdom. As our subsequent essays will explore, this maturation requires understanding thermodynamic realities, accepting irreversible changes, learning from suffering, and transforming consciousness regarding our place in the biosphere.

The adolescent is not evil for being immature. But the adolescent must eventually grow up or face consequences of perpetual juvenility. Industrial civilization stands at this juncture. The diagnosis is obvious. The prescription begins with acknowledging the condition.

Read the series introduction and access the other essays.

References

Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G., & O’Donoghue, T. (2002). Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 351-401.

Giedd, J. N. (2004). Structural magnetic resonance imaging of the adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1021(1), 77-85.

Goleman, D. (2009). Ecological Intelligence: How Knowing the Hidden Impacts of What We Buy Can Change Everything. Broadway Books.

Leonard, A. (2010). The Story of Stuff: How Our Obsession with Stuff Is Trashing the Planet, Our Communities, and Our Health. Free Press.

Leopold, A. (1949). A Sand County Almanac. Oxford University Press.

McNeill, J. R. (2001). Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World. Norton.

Micklin, P. (2007). The Aral Sea disaster. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 35, 47-72.

Pauly, D. (1995). Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 10(10), 430.

Pierrehumbert, R. T. (2015). Climate hacking is barking mad. Slate. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2015/02/

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin, F. S., Lambin, E. F., … & Foley, J. A. (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461(7263), 472-475.

Rogers, G. (2025). Manifesto of the Initiation. Coldwater Press.

Shepard, P. (1998). Nature and Madness. University of Georgia Press.

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., … & Sörlin, S. (2015). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347(6223), 1259855.

Stern, N. (2007). The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge University Press.

Stone, R. (2011). Mayhem on the Mekong. Science, 333(6044), 814-818.

Weinstein, N. D. (1980). Unrealistic optimism regarding future life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 806-820.

[Read the series introduction and access all nine essays here.]