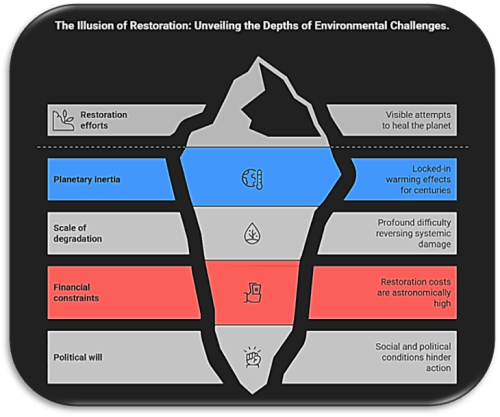

In the grand narrative of our species, we have arrived at a pivotal, sobering moment. The Earth’s biosphere, a delicate and complex tapestry woven over eons, now bears the deep imprint of our civilization. A noble and understandable impulse urges us to restore the planet to its former glory, yet a clear-eyed look at the evidence suggests this may be beyond our grasp. The inertia of our planetary systems is immense; even if all greenhouse gas emissions ceased today, significant warming is already locked in and would persist for centuries as a new equilibrium is slowly reached (King et al. 2024).

The sheer scale of the challenge is written upon our landscapes and in our waters. Consider the Chesapeake Bay, once North America’s largest and most productive estuary. Despite decades of concerted effort and billions of dollars in investment, its ecological health remains precarious, a testament to the profound difficulty of reversing systemic degradation (Rust and Blum 2018). Look to the Amazon, the lungs of our planet, where the cost to restore even a fraction of what has been lost is estimated in the hundreds of billions of dollars (Lennox et al. 2018). The financial and political will for such an undertaking on a global scale is simply not present.

The very social and political conditions that hinder restoration are the same ones that will impede large-scale adaptation. It is time, therefore, to pivot our focus toward achievable survival strategies. This is not a message of despair, but a necessary recalibration based on the evidence before us. We must learn to navigate a new world, one where our role is not to restore the past, but to thoughtfully and ethically adapt to the future we have created.

References

King, A. D., et al. 2024. Exploring climate stabilisation at different global warming levels in ACCESS-ESM-1.5. Earth System Dynamics 15: 1353-1383.

Lennox, G. D., et al. 2018. Second rate or a second chance? Assessing biomass and biodiversity recovery in regenerating Amazonian forests. Global Change Biology 24(12): 5680-5694.

Rust, S., and Blum, S. 2018. Chesapeake Bay: A journey to restoration. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/pages/interactives/news/chesapeake-bay-a-journey-to-restoration/